Representation matters. It’s powerful to see yourself in the media, images, and icons that surround you. The more you see yourself, the more likely you are to see diverse stories about who you can be. Yet in 2020, artists represented in US art museums are still 85% white and 87% male, and women of color collectively make up less than half of one percent of art collections.

This AAPI Heritage Month, I had the honor of curating a panel discussion for American Family Insurance. While the livestreamed panel was a part of educational programming for Am Fam’s workforce, the artists’ insights were so on point that I’m sharing them here for posterity. Thank you to all the artists for sharing your stories and perspectives and expanding representation for our field.

Meet the Artists

Your mother once reminded you that when you talked about what you wanted to do when you grew up, you said, “I want to make art to bless people.” How does that statement relate to your work today?

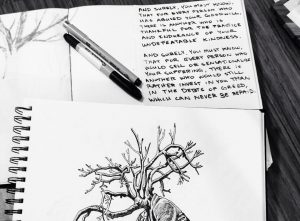

Leslie Iwai: At that time I didn’t know that I would end up as an artist, but that statement means so much to me! I have always wanted people to encounter my work through their own stories and that through my work they feel seen and cared for. I hope to touch on universal themes that can become highly personal to each individual as I bring my own vulnerability to each project. Right now I am working on an installation that is titled Winter’s Spring: An Ältere Garten. I am merging imagery of childhood and aging in ways that brings honor to our elders as many have a recurrence of childlike wonder in their winter season, I am seeing this in my mother as she now has dementia. A sculptural element of this is a set of five 17’-20’ white tulips that have the color on the inside of the blossoms. I am also highlighting a friend of mine that is in her eighties that has had a garden for over fifty years and has kept a written and artistic journal of it for twenty years.

In terms of blessing people with the work of my hands I often think of my Japanese grandma, my father’s mother, who lived in Hawaii. She was an excellent seamstress, sewing the clothes for all her children and teaching others to sew as well. Since I primarily grew up in Nebraska, she didn’t teach me but I saw my dad hemming all his pants! Sewing is a big portion of my sculptural work – I think my talent and ability to craft so well with my hands is from my grandma. I have a lot of her patterns she used and a pair of her sewing shears.

Your work has always been about our relationship with language, but not always about culture. How and why did this change when you moved to the Midwest?

Helen Lee: There were two factors that played into this. I had never lived in the midwest before. I grew up in Jersey and spent a decade in New England, and nearly another decade in CA in my early career. In all of these places, there was a critical mass of Asian people. I had never lived before in a place as culturally homogenous as the midwest. Even the “white” suburb where I grew up had a lot more diversity than here. “White” meant Italian-American, Greek-American, Irish-American, Portuguese-American. All the summer festivals in my town were cultural festivals. Everyone was still only a few generations out from their cultural heritage. Moving to the midwest was an exercise in having my cultural background thrown in my face on a daily basis, whether I liked it or not. So it was somewhat unavoidable I had to think about it in ways I hadn’t before.

Secondly, I decided to have a kid. That’s a huge threshold for anybody to cross. My partner is Caucasian, but what really made this threshold feel vast was that in my case, I had already lost my parents and grandparents. It wasn’t possible for me to move forward into the future without combing through my past and thinking about the distance that will grow between my daughter and my cultural background. I often think about how every single day is a small act of mourning from an immigrant-American perspective. As I approached parenthood, the generational shifts in relating to one’s culture really emphasized that feeling and saturated every aspect of my life, including my studio practice.

You’re working on a graphic novel right now, about a Vietnamese-Indian superhero. Can you tell us more about this work, and why you’ve chosen to tell this story using comics as opposed to another art form?

Noah Laroia-Nguyen: I am creating a comic about a superhero named Garuda, which is also the name of a Hindu deity and Indian cultural symbol of protection. Her power is in her blood quite literally because she has gold blood which can be turned into objects like weapons, shields, etc. For me comics is an ideal medium for a number of reasons. It is of course where superheroes originate from and where we are used to seeing them. It is also a story driven artform which means both the characters and I can develop, grow, and learn as the story continues. Most importantly though, comics were one of my first artistic influences. Growing up I would copy drawings from comic books at the library, and that is how I taught myself to draw. The thing I always felt was missing, even as a kid, was that there were no superheroes that looked like me, or who had a name like mine. And I think that sort of thing had a big impact on me and I’m sure it had an impact on a lot of other people. So my goal for this project is just to get more brown heroes out there. My youngest cousin is three years old right now and she is the same mix as me. Her dad also loves comics and I’m sure he will try to pass that on to her in some way. And when that happens I want my little cousin and future kids in my family to enjoy comics the way I do and feel like there is a place for them.

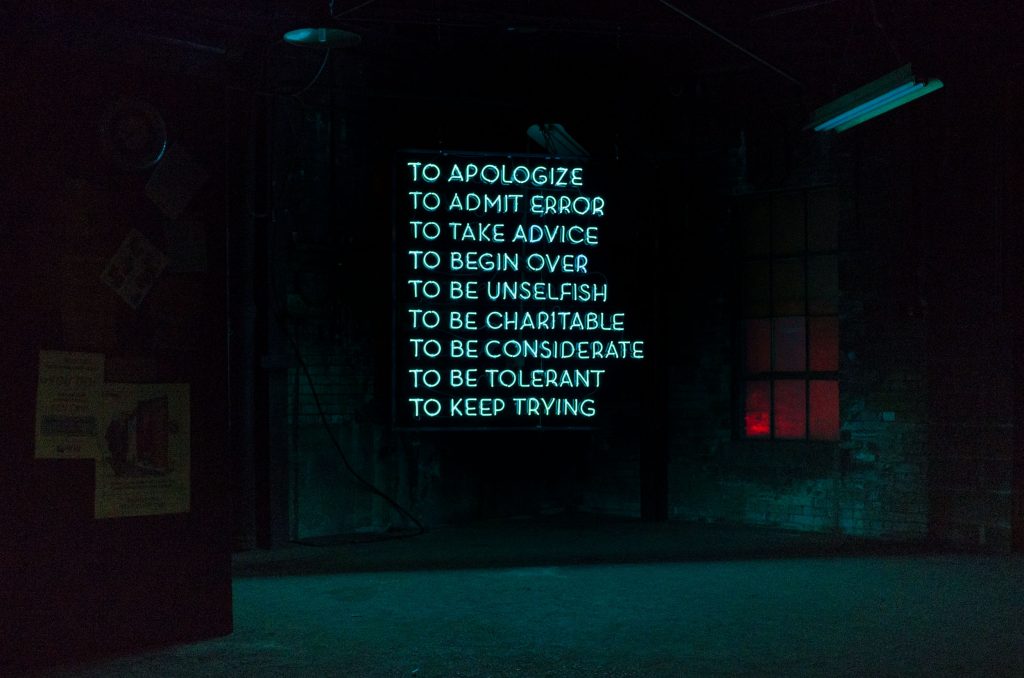

Miscategorization of people’s identities is a major theme in your work, as well as invisibility/visibility. Can you give an example of how miscategorization has affected you? How does this impact the work you make?

Maeve Leslie: I have many examples of miscategorization that range from kind of harmless to more scary. Sometimes I have people walk up to me and assume I speak a certain language or are surprised by my appearance when they imagine what someone with my name must look like. I think my worst experience was when I had a dentist replace a filling and they gave me the incorrect dosage for novacaine. When I asked about it, they just said that my genetics “must not align with the typical Asian dosing standards” and requested that I “mark Native American on the paperwork from here on out”. I’ve also had a few incidents since moving to Wisconsin, such as being asked about my citizenship on my commute, that I’ve never had before. These experiences have prompted me to put my identity more front and center in my artwork. Through questioning and miscategorization I have chosen to tell my story how I want it to be seen and heard before the invisibility is placed upon me. My work is often nuanced and coded for specific members of my audience as a way to connect through the art, but it’s not meant to be exclusionary or prohibitive. I look at my work as a way for me to physically and conceptually hold space for the invisibility and miscategorization I and others often experience.

You say your work is about claiming space and creating records of stories and identities we might otherwise miss. How does this manifest in your work?

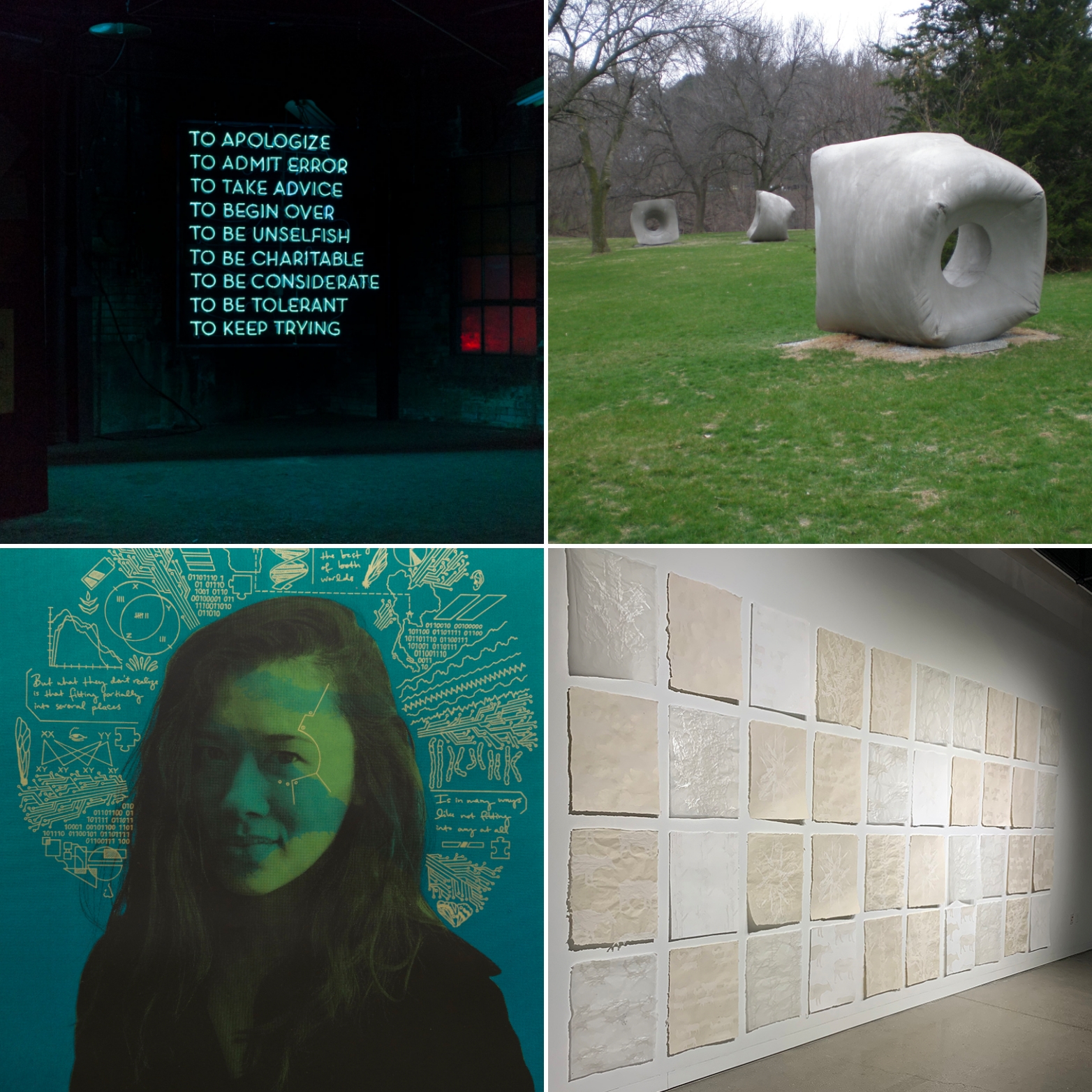

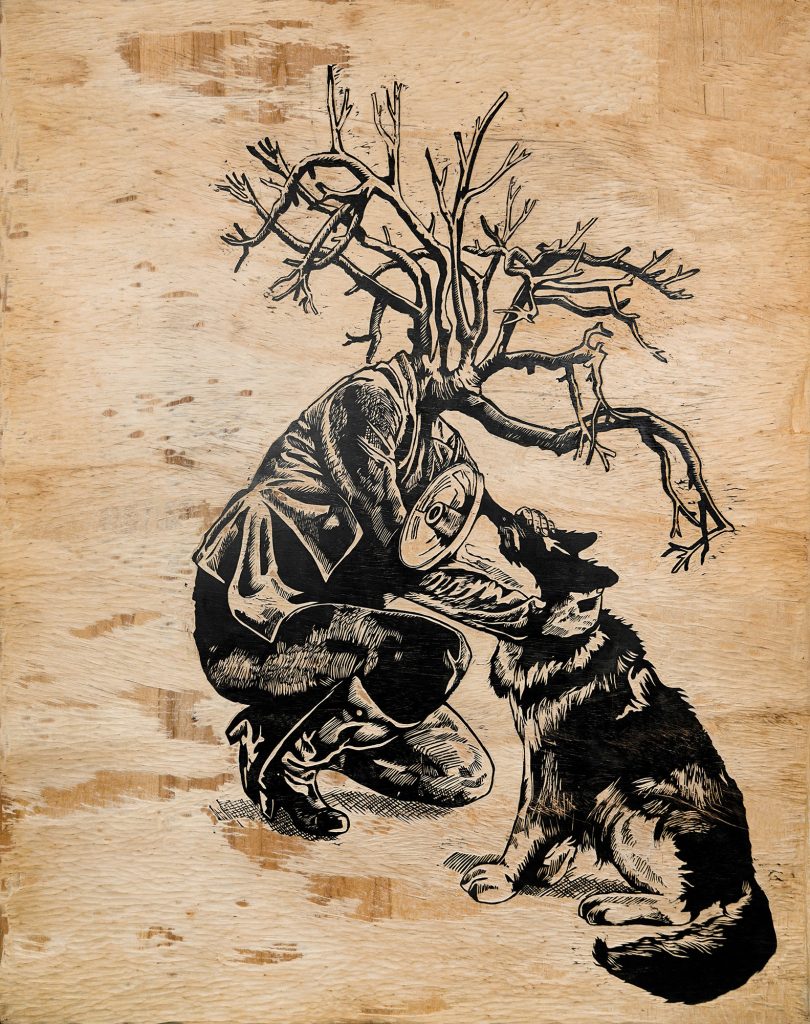

I’m drawn towards democratic mediums. I became a printmaker, with a specialty in woodcut, because of the democratic history of print. The invention of print democratized education and literacy as we know it. It was through print that I also became interested in working at scale. You can make multiples of the same print to take up real, physical space, and also take up mental space through the mass sharing of a message. It was a pretty natural transition for me to go from working in woodcuts and printmaking to murals and installations. Murals and public art are another democratic medium. They take up physical space in a public setting and change the way people interact with that space. Public art tells us visually and spatially, who belongs in that space. So for me, as a woman and an entrepreneur in the arts, it feels incredibly powerful to harness the mediums of art, storytelling, and commerce, to change what people see in the spaces they occupy and the value of the people who exist in that space.

On Heritage

Tokenism is the practice of recruiting minority groups into a workforce and only including them symbolically, to give the appearance of equality without actual change. Tokenism is one of the challenges that faces even well-meaning attempts at diversity and inclusion. What are some ways we can avoid tokenizing people when creating space for diverse stories?

Helen Lee: Well-intentioned attempts at diversity and inclusion are really prevalent. There are a few filters that come to mind that could help this problem. The first is improving our listening skills. I think listening is an underdeveloped skill in the US, and it’s a critical necessity to move past tokenism. Secondly, I think people need to be more aware of whether they would assign a racial identity as important if it weren’t someone Asian. It drives me particularly nuts in the midwest when my cultural background gets irrelevantly dropped into a conversation to cash in on some diversity points. People need to think very critically about their own reflexes in this regard. Lastly, I think putting people of color in positions of power is really important, all-around. This also gets complicated with respect to tokenism. From a social justice frame of mind, it’s important to be cognizant of who holds power in any given situation. This gets complicated when power is conflated with tokenism. Who holds the power in that situation?

Leslie Iwai: This is complex but one of the main things is that when someone is invited to the table expect them to bring their story with them. Know that it might not have anything to do with what would check a certain box or fulfill some possibly preconceived idea of what one hopes looks a certain way or contains certain cultural symbols. I think the beauty in diversity and inclusion is the unexpected- the nonlinear connections that are discovered between the wide swath of humanity. If there is a pre-scripted expectation I am very apt to not participate, sensing confinement and devaluing of me as an individual.

This question also reminds me of a story my dad shared with me about his work. We were in the midwest and my dad was working for the Army Corps of Engineers. He told me once that people would ask him how he felt as Japanese American in the office. He told me that he responded to them, “Well when I look out all I see is you all (primarily Caucasian Americans), I don’t see myself “. This has stuck with me for years (he died about 23 years ago). I had always thought how he wasn’t as aware of race – his race- as others were about it. As the years pass, I wonder more about that statement. He was just doing his job, living his life. I imagine that when he was growing up in Hawaii among many other Japanese Americans he would never have been asked that question. I don’t believe that he wanted to stick out, have extra attention on him- but I do think it was a glimpse into what not seeing others reflected in the world around you is like and how that might bring unwanted attention.

What’s your relationship with immigration, and how has your family’s immigration story led where you are today?

Maeve Leslie: Immigration is something prominent and often talked about in my life. In the Philippines it is almost customary for someone in the family to be an Overseas Filipino Worker (OFW). This often means individuals leave their families to work outside of the Philippines in various jobs. My mother was an OFW and took a job in the United Arab Emirates. She was housed and fed and sent all her additional income to her parents and family in the Philippines. From there she was an Au Pair in France, then she moved to Canada where she met my father, they went back to the states where she became a US Citizen and I was born shortly after. These various cultures and cultural experiences played out in my upbringing and are still a major part of my life. I am constantly reminded of living conditions and the lack of opportunities for my family members who are still in the Philippines. I am also often used as an example for my many relatives. For example, because I went to college the rest of the family should strive for the same level of education. Bottom line, I would not be here if my mother had not left the Philippines. I have recently been documenting and doing research regarding my mother’s own immigration. On our most recent visit to the Philippines we traced her route from her childhood home to the airport where her immigration journey began. This is one way I get to connect with her and try to understand how she got to where she currently is. It’s also the best way for me to experience what she went through in a way that I probably never will.

Noah Laroia-Nguyen: My family has two different immigration stories. My mother immigrated from India in her twenties to go to grad school and start a career in food science. My father came to America as a refugee when he was thirteen. Because of that difference they have two very different life outlooks, even though they are both immigrants, and parts of both views get passed on to me. My mom has the more stereotypical immigrant outlook. Her immigration was an investment so everything is planned and there is a guideline you follow. On the other hand my dad sees everything as a blessing because he feels lucky to be anywhere at all. When I was choosing to become an artist that made my mom apprehensive because she felt like this strayed from the plan and safe investment that had been made. My dad was very supportive though because he felt like this was an opportunity that he would never have had so I might as well go for it.

Being an artist doesn’t usually fall within the stereotypical career choices for Asians. Why do you think that is? Why is it important to increase Asian representation in the arts and overcome this?

Jenie Gao: There are a few reasons why. The first is the stigma associated with the arts. We live in a world where the stereotype of the “starving artist” exists simultaneously with the notion that “art is for the elite.” The “starving artist” implies that artistic labor is not valuable and not something you can be compensated for. “Art is for the elite” implies that the art itself, the property, is valuable, and that art is only to be enjoyed by society’s elite. So the only way to be an artistic laborer is to either starve for your craft, at the exploitation of your labor, or to be born wealthy enough to not need the income. Because of this stereotype, it’s not just Asians who don’t pursue artistic careers. It’s the working class in general, and particularly working class immigrants who often move here in search of a better life through upwards social mobility.

The second reason has to do with the stereotypical careers that are reinforced for upward mobility. The “model minority” careers for Asians tend to be the sciences, engineering, tech, and medicine. What most people don’t know is that the “model minority” was intentionally designed. The US banned Chinese immigration in 1882 through the Chinese Exclusion Act, then extended this ban to all Asian immigration into the 1900s. It wasn’t until 1965 that these bans were lifted. What else was happening in the US in the 1960s? The Civil Rights movement. The US began selectively, intentionally allowing specific Asian professionals to the US: doctors, engineers. They did this to prove that anyone could succeed in America as long as they worked hard and were compliant. This narrative pitted Asian immigrants against other non-white groups, and excluded the vast majority of Asians who do not fit the “model minority” myth. To this day, we have a very narrow, contradictory perspective of AAPI identity as a result.

Noah Laroia-Nguyen: I think there are two major sides to this. The first is that there are a lot of barriers to becoming an artist. Specifically wealth and race which Jenie talked about. The other side is that there is a lot of pressure from the Asian American community in terms of what jobs and careers to take on. Many of us are the children of immigrants and our parents have sacrificed a lot to advance to the point we are at. There is a lot of pressure from family and community to have a job that is safe and being an artist is inherently a risk. You don’t always know if you’re going to make it. In terms of the racial barriers to entry, there is also a sort of feedback loop. Younger Asian American artists or even people who are deciding their careers get discouraged by the fact that there are not a lot of other Asian American people in the art world. Having a mentor or peer that shares your experience is something that makes any career path more comfortable. Because of that I think it is important not only for us to encourage more Asian American kids to pursue their interest in art but also to put our Asian American artists in the spotlight.

We tend to build “racial monoliths” in the US. For example, we treat all Asian ethnicities as the same, even though there are over 30 Asian ethnicities and nationalities represented in the US. The AAPI umbrella contains a plethora of diverse ethnic groups and experiences. Could you share a story or an example that challenges mainstream perception of AAPI people?

Leslie Iwai: Once someone came into my studio and expressed emphatically that I should do a tea ceremony as part of one of my art presentations. I grew up in the Midwest where certain practices from my father’s (Japanese heritage) were embedded in our daily lives but tea ceremonies were definitely not one of them! Yes, we drank green tea (ocha), ate rice and Sukiyaki and took off our shoes before entering the house but we also played soccer and ate chocolate chip cookies. I have also experienced the situation of shaming and disappointment that comes my way when I am asked about my knowledge of the Japanese language (I didn’t learn any-neither did my Japanese American father due to Japanese language school closures during WWII).

I am also asked, often by non-Asians, if I have been to Japan and told how important it is for me to go. They tell me how beautiful it is, how inspiring it would be to me as an artist… I have not gone to Japan. What I want to say is that it is expensive, I would like to go but life circumstances have not made for this reality yet – that my main Japanese side of my family lives in Hawaii and I when I can travel a longer distance, I have chosen to spend my time and income visiting them. My grandfather was born in Hawaii in 1900, so our family has a lot of history in the American story of the last 100 plus years, as a fourth generation Japanese American I see my mixed racial background as a complex and beautiful story, one not to be easily categorized by racial tropes or stereotypical expectations.

Maeve Leslie: I’m currently reading “The Latinos of Asia” which investigates and challenges this idea. The quick summary of the book so far is that Filipinos are often lumped in with the Latino population instead of other East Asian countries that Asia is more often stereotypically associated with. The opening anecdote is about the author signing up for a study about Asians and alcohol. The researchers were going to sign up the author for the study until they found out he was Filipino which disqualified him because they needed subjects of a “genetically similar sample” which in this case meant Chinese, Japanese, or Korean. Even growing up I had others tell me that the Philippines was in Asia but that didn’t really make me “Asian” because I did not fit the typical idea or look of an “Asian Woman”. Or because my family didn’t use chopsticks we weren’t “really Asian”. I can also empathize with Leslie by not knowing my perceived native language and only being able to communicate in English. My father forbade me from speaking anything but English and my mother wanted to improve her English because she was living in America. In the Philippines everyone is taught English due to colonial contact, but my mom knew she needed to expand her vocabulary in order to “do better” and did that through me while I learned English in America. I think it’s valid that there are similarities between the different cultures of Asia, but to place an “assumption umbrella” on all Asian people is not realistic. Even within individual countries of Asia there is vast diversity. For example, the Philippines is made up of over 7,000 islands and 100 languages. If you order a Filipino dish in the northern part of the Philippines, it could have a variety of spices in it where the same dish in the southern part could have more herbs and coconut milk.

What’s something you would like to see change about AAPI representation in the US?

Helen Lee: A topic I’ve been turning over in my head a lot lately is what people of AAPI descent are “supposed” to do with their narratives of trauma. I think one of the most damaging aspects of the model minority myth is that there isn’t any room to discuss how ugly the trauma and intergenerational trauma can be. This is likely the case in any immigrant population, but overlay onto that the cultural proclivities around shame and saving-face from many AAPI cultures, and you’ve got a double vacuum of silence, which evaporates any hope of healing this trauma. In Cathy Park Hong’s recent Minor Feelings, she writes of Asian representation on TV, “I’m of the extreme opinion that a real show about a Korean family—at least the kind I grew up around—is untelevisable. Americans would be both bored and appalled. My God, why can’t someone call Child Protective Services! they’d shout at the screen.” A change I’d like to see in AAPI representation is more space for these narratives and ugly truths to exist. I think it’s interesting to witness the timeline of someone as canonical as Amy Tan. Her debut novel came out in 1989. But it’s taken 30 years for it to feel right for her to speak to her personal trauma directly in her 2017 memoir.

Jenie Gao: The author, Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie, talks about the danger of the single story, where you reduce the entirety of a people’s experience to a single narrative. She gives the example in her TED talk of a fan approaching her after reading her book and saying how unfortunate it is that all Nigerian men beat their wives. Adichie retorted that she had recently read American Psycho, and how unfortunate it is that all young white men in America are serial killers. Now she was being facetious, but the point she made was that nobody worries that American Psycho will damage the image of all white men, because there are lots of stories that represent white men. There are very few published stories that represent Asian Americans. So, following on what Helen said, this makes it even harder to talk about AAPI trauma, because what if you tell this gushing story about all the bad things that happened to you and Americans, particularly white people, think that your trauma is all you are? What if instead of healing you, sharing your trauma invites others to judge you?

4.5 billion people, almost 60% of the world’s population, is Asian or descended from a country in Asia. And yet we call Asians the minority. The highest grossing movie about Asians is about Crazy Rich ones, reinforcing the stereotype that all Asians are doing well, while we all walk around with smartphones made in a factory with labor conditions so bad there are suicide nets. The stereotypical image we have in our minds is of a dutiful, Asian student who goes into a dutiful career, and so we miss out on the revolutionaries and the leaders. Asian Americans still enter politics at a lower rate than other people of color. So I guess I’d like to see our representation expand to a multitude of stories, and for us to be seen as complex people who are bigger than one heritage month could ever represent.

If this interview resonated with you, be sure to follow and support all of these amazing artists.