My mother once told me the story of a cartoon she saw in a newspaper some years ago, which explained God.

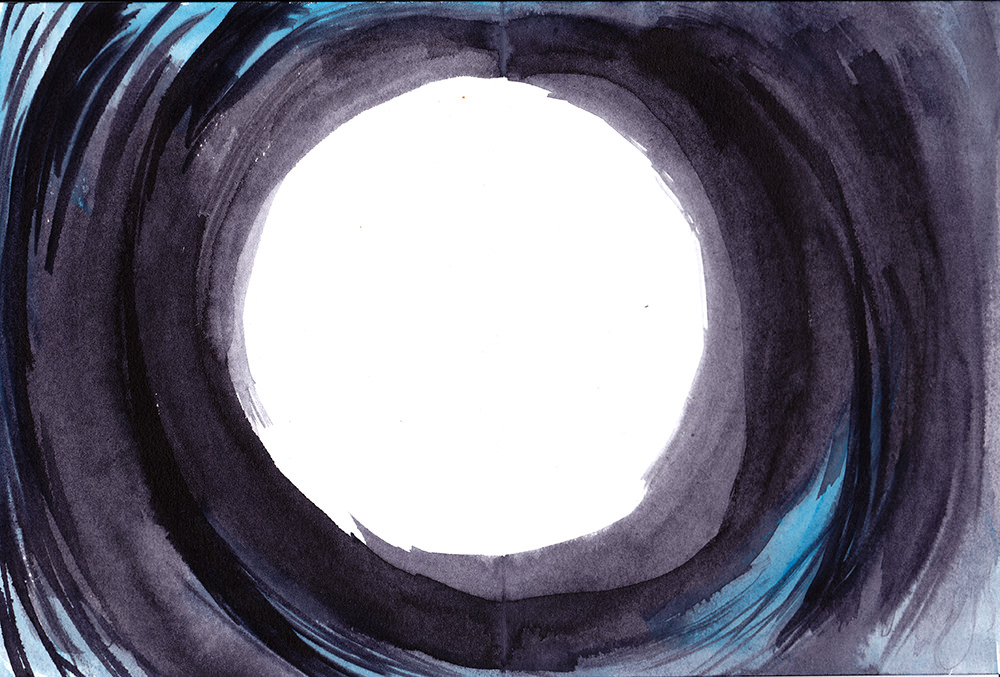

In the cartoon, God is a faceless, featureless oval on a table. People come to see and give thanks for all that God has done. They see that God has nothing, no way to see or feel or hear or think. So out of gratitude, the first person gives God a mouth, the next a nose, the next ears, and finally, when God has all the qualities that people have, God dies.

Every once in a while, my mind drifts back to that cartoon whose message I learned secondhand, and the ways one can interpret it.

It implies the same things as the sayings, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions” or “No good deed goes unpunished.” It bears the ideas of how we, as people, can often try to fulfill needs that don’t exist, offer unsolicited advice, promote solutions that worked for us but may not work for others, or in general do things that evidence how we need so badly to be needed. All of which I think reveals our generosity more so than our selfishness, is more exemplary of our desire to be valuable and useful than of our ignorance. We want to relate and we want to be relatable. We want to find ourselves in others. And so it is that we may also want to design God–or whatever our beliefs may be–in our own image, not purely out of egotism, but out of some sort of self-validation or even vindication.

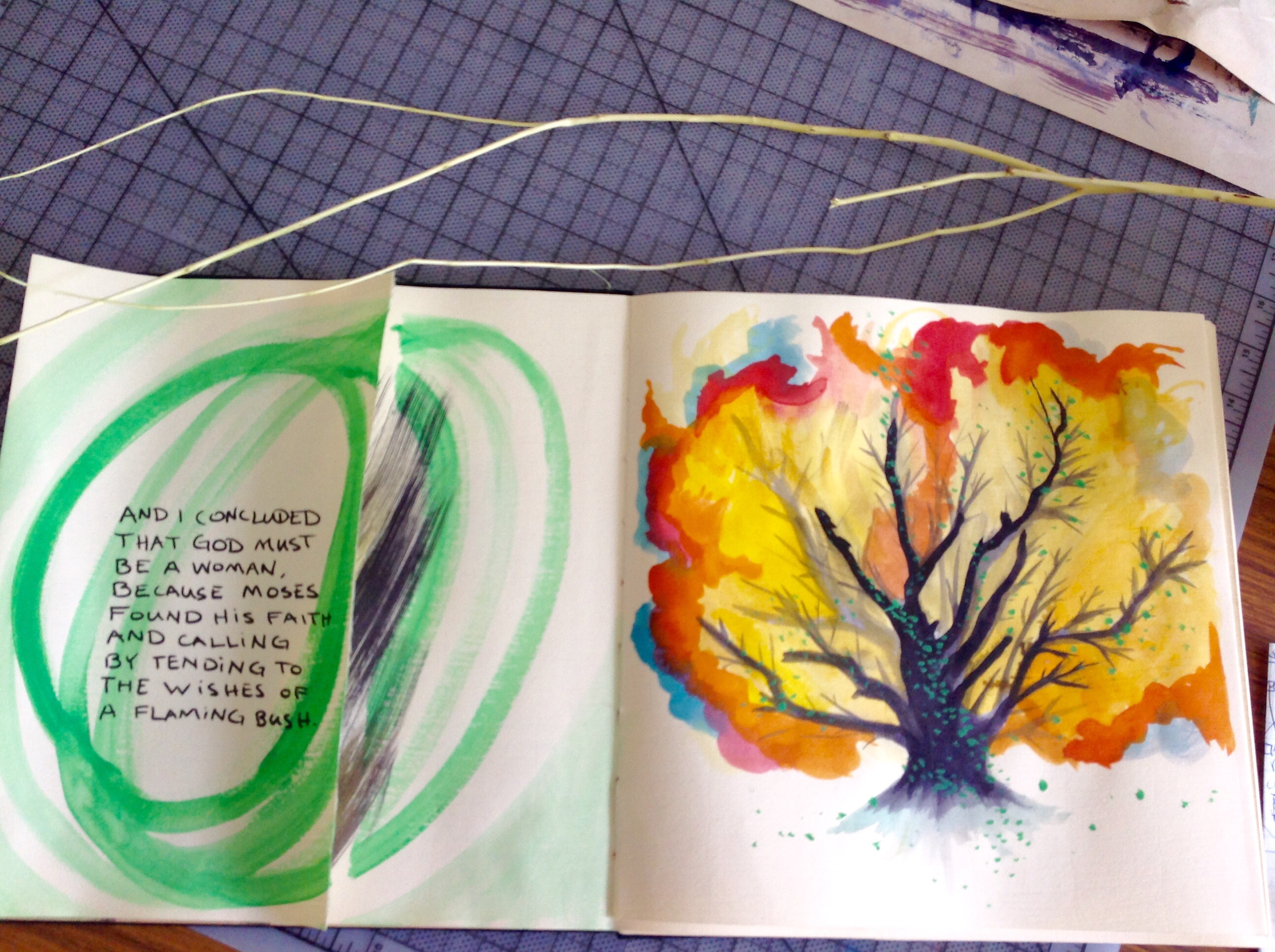

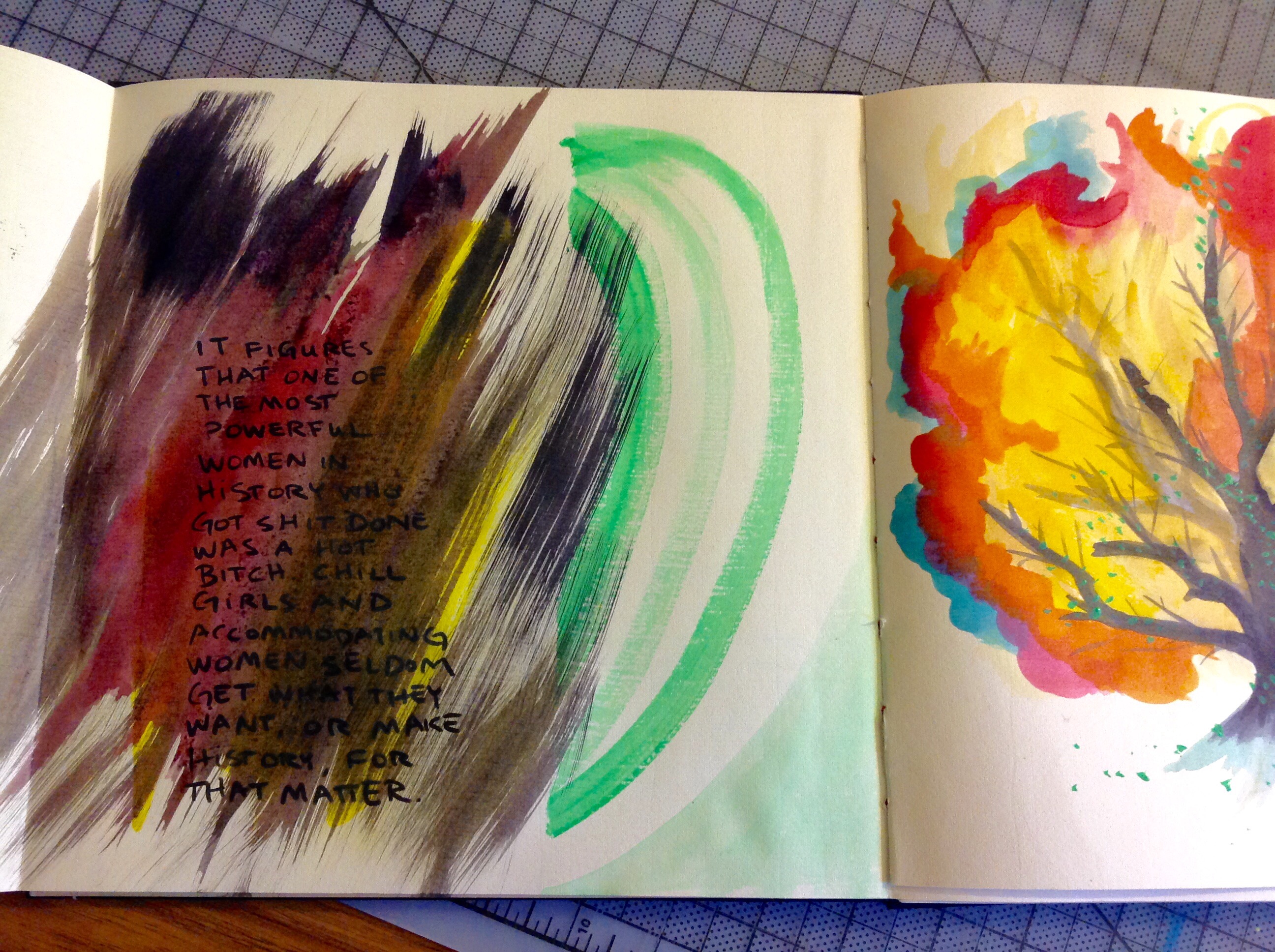

Of course, other times, my thinking is a little less…philosophical. Like on this warm, summery day, while I was out for a run, I thought about romance, gender wars, and whether God is more manly or womanly. And I concluded that God must be a woman, because Moses found his faith and calling by tending to the wishes of a flaming bush.

It figures that one of the most powerful women in history who got shit done was a fiery, hot bitch. Chill girls and accommodating women seldom get what they want, or make history, for that matter.

To believe and not believe

I grew up in a non-religious family, though many of my extended family members and hometown community (Kansas, for the record, heart of the Midwest) were very religious. And for that reason, I grew up with both the chance and the motivation to choose, a la carte, the things that made sense for me. I grew up with more questions than set-in-stone facts, because anything and everything that a friend, neighbor, or relative might believe in could be challenged by what another friend, neighbor, or relative valued. I grew up without celebrating holidays, which pushed me to ask myself what I would want out of the kind of gatherings that others felt so obligated to be a part of.

We did not celebrate birthdays in my family, or pray, or “break bread” together, and so I think I came to hunger for the rituals and acts of gathering that happen around those things, but not for the fluff or the stuff. As a result, there are few things I cherish more in my adult life than a meal with friends. And few things sadden me so much as any kind of meet-up, where despite everyone being bright and interesting in their own right, the social energy is somehow amiss or misdirected, and the loneliness/guardedness in our advanced and blessed society is so obvious.

Anyhow, as someone who grew up surrounded by a lot of religion despite not having one, I was asked and therefore made to reflect on whether I believe in God. It’s safe to say that I am in many ways a ritualistic person, and that I’ve pursued a lot of unlikely dreams, which requires faith against the skepticism of the “known” world. My answer to believing in God has changed over the years, and for the majority of the time I’ve probably been agnostic. But I have since concluded that yes, I do believe in God. I believe in the way that I believe in money.

What I understand is this: money exists because people agree that it exists, and what we collectively believe in becomes the truth. Money–like so many of our creations–could be the great equalizer. It gives us an objective measure so we don’t have to question what part of our lives is worth four cattle or ten kilos of tomatoes. It’s part of the agreement of living in a collective, a society with rules and infrastructure. Enough of it buys us freedom and teaches us responsibility. Too much or too little both destroys freedom and incites blame. But when we add distance between ourselves and the true value of the things we exchange and consume–while developing an overly-emotional attachment to this thing called money that by itself means nothing–money becomes evil and we become lost.

Like money and all the things we try to organize ourselves around, I think God has the chance to be a great equalizer. I don’t believe God is capable of existing without people or the living. Even if God were an old, white man in the heavens in the most traditional, Western sense, there wouldn’t be much to lord over without us. Regardless of what or who God is, it’s important for us as people to have something to believe in, some purpose to serve and strive for. “I am who I am,” said God to Moses, because God is not a name but a representation of what we care about, a term around which we can organize our understanding of this connection whose feeling we know but cannot easily explain. “Say this to the people of Israel, ‘The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you.’ This is my name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations.”

And so it is that we are responsible for creating God in the image of whom we would like to become. We are responsible for being just if we expect justice. We are responsible for choosing the qualities that we value in our leadership. We are responsible for our individual thinking, that fractals out into the design of our collective imagination. We are responsible for a creative and smart God who takes after us, because we take after Them. And we are responsible, too, for a God who embodies that which we lack, for the people we are not, but coexist with. For the people we are not, but wish to be. For the people we are not, but that our children may become.