It was 1991. I was three years old. My dad was in Seattle and my mom would be alone with me that winter.

The road was covered with ice on her morning drive, and when she parked her car to drop me off at preschool, she was scared to get out and walk with me across the pavement.

When she opened the car door for me, I jumped out immediately, and in alarm, she yelled, “Be careful! Don’t fall!”

To which I responded, “Don’t worry, Mommy! You can hold onto my shoulders. I’ll help you walk across the ice.”

I don’t remember this event, but my mom does, and she remembers the comfort she took in seeing how brave (read: foolhardy) I was, at a time when she felt low, powerless, and lost. All I remember, of course, is how annoyed I was in my early teens, that my mom needed to take my arm in a death grip every winter, whenever there was ice. I complained that she was going to take me down with her. I didn’t know that she was seeking comfort and security in me.

She didn’t tell me this story until yesterday, and who knows, maybe it wouldn’t have had the same gravity (ha) before I reached the age that she was in this story. Whether she intends it or not, through all of her stories, she impresses upon me the understanding that she (and potentially anyone) is paying attention. She’s learning from what I do, and in the process of changing myself, I change her as well. Our unconscious actions are teaching moments, in partnership with the things we say.

When we’re children, we don’t know what our parents don’t know. We don’t know about the size of their fears or failures. We don’t know how much they both cherish and judge us for our ignorance that convention has named innocence. We don’t know that our ignorance is teaching them how to be parents, that we are their test. We don’t know whether they’ll pass this test, whether they’ll choose to protect our “innocence” or feed our curiosity. We don’t know that their compulsion is to keep us safe, but that their job is to teach us how to overcome our ignorance, to be cognizant of our impact, good and bad. We don’t know how difficult of a job that actually is, both to carry out well and then let go of.

And once we do know all of this, we still aren’t necessarily prepared to face the next challenge of growing up, which is to get over the fact that for all our experience we still don’t know, and yet we have to keep going. We have to fight the urge to hide our weaknesses or let them be our limit. We have to fight the urge to be lazy and use arbitrary qualifiers like age to measure our growth.

There is the child who says, “Don’t worry, Mommy! You can hold onto my shoulders. I’ll help you walk across the ice.”

There is the teenager who says, “Don’t hold me. You’re going to take me down with you.”

There is the adult who knows what the teenager knows, the risks and the consequences of being wrong that the child has yet to learn, who then must choose to step up and say, “Don’t worry, you can hold onto me,” and then step down and say, “No, I haven’t been here before. No, I don’t know if we’ll be successful. Yes, I am scared of letting you down. Yes, I’m scared of you letting me down. But yes, I will still help you.”

And be willing to ask, “Will you also help me, and us, cross the ice?”

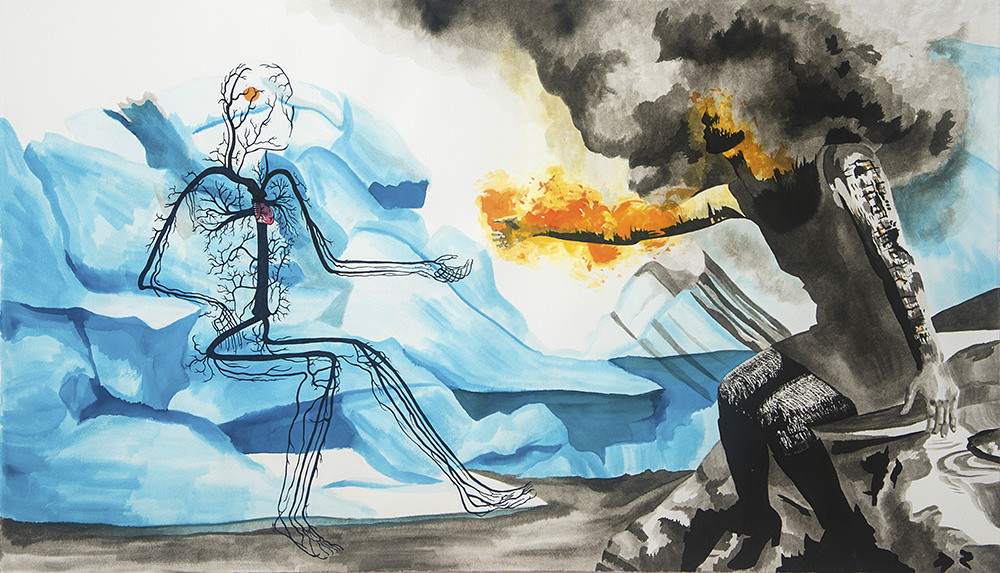

**Featured image is “Counter Intuition,” part of my series of ink drawings, “A Test of Vision.”