February 8, 2017, would have been my dad’s 66th birthday. He has been gone for nearly 8 years.

I have been thinking a lot lately about things that come in twos.

Things set in opposition that are necessary parts of a whole. Left versus right, male versus female, north versus south, conservative versus liberal.

Things that intersect or prove simultaneous truths. The intersection of two roads. A house on a row, adjacent to two other houses, that is simultaneously both their neighbors. The invention of printing, which is both an art form and a technology. Multiple identities, which we associate with people being multiracial, inter-religious, gender-fluid, bisexual. Or the running joke among people who hate identity politics is “I don’t care if you want to be a purple alien unicorn.” But multiple identities could just mean that being a mother and a wife doesn’t mean you cease to be a daughter. Identities don’t exist in silos.

Things that do not intersect, but inform or create each other. The past and the present. Parallels between different times in history. Correlations in data. Your reflection in a mirror. The reversed image of a stamp, pressed on paper.

Earlier this year, I turned 29, the same age my dad was when he immigrated to the United States. My 29th birthday took place a few days after Martin Luther King Day, the same day as Inauguration Day (1/20), and the day before the historic Women’s March.

As my father’s birthday passes once again, just one day after the confirmation of Betsy DeVos as our Secretary of Education, I can’t help but think about the significance of my role as an educator amidst political turmoil.

I am thinking about his old stories. He was born shortly after Mao Zedong’s rise to power in China. He was the first generation to be raised by state educators instead of by his parents, so the adults could be dedicated to serving the Communist Party and military. He was of the generation that lost its education to the Cultural Revolution, when the schools shut down and the leaders accused the teachers of instilling radical, elitist ideas upon the youth. My dad had always been a terrible student, had failed grades, and been held back multiple times. The teacher who had succeeded in reaching him and led him to becoming a top-performing student had done so by encouraging his love of literature.

The leaders of the country had incited the youth to turn against their teachers. The schools closed. My dad was among his fellow students the day his former teacher and mentor was condemned as an “educator who was corrupting the youth.” He was among them as they gathered around her, to beat her. And he pretended to beat her, too, though did his best to stay in the middle of that crowd, to stand between her and the blows of his peers.

That was just one of the events that took place the year my dad’s education ended. He was in the seventh grade, and only by a fortuitous and unlikely series of events was he able to study English in his late twenties and come to the United States.

I can’t help but think about what it means for me to be a teacher now, all these years later, at the same age as he was when he finally got to be a student again.

And that continues to be the main difference between the past and the present, that one generation of students will become another generation of studies. History will be the student of what it later needs to teach.

It is bittersweet for me, now, to look at my dad’s manuscript about his life in China, and read the paragraph about him receiving his passport, which read, “To All Countries in the World.” It is bittersweet to imagine how it must have felt for him to read those words as China re-opened to the West. To imagine how it must have felt for him to write that, decades later, knowing that for over two decades, he never did make it to Europe, and never got to live outside of Kansas again.

My dad would spend half his life in this country. He would spend many of those years dreaming of becoming a writer, trying to recapture the history and the lessons of his youth, the lessons he learned growing up in a country full of contradictions, the lessons he learned from a Cultural Revolution that built up and destroyed the hopes of his generation within the same uplifted blow. He would spend many of those years frustrated by the limits of a man who was robbed of his early school education and basic foundations of mathematics and science, and yet extremely educated in his mindset and well versed in US and global history, dreaming and wondering what the worth of his story might some day be.

And he, along with my mom, would tell me how lucky I was to be born here. How lucky I was not to speak English with an accent. How much easier I would have it than they did. Especially as a girl. Especially as a girl after China’s one child policy, which was implemented in 1979, the same year my dad moved abroad.

When the world tells you you’re lucky, you can’t help but agree. You also can’t help but overcompensate for that luck, to really want to prove that you deserve to be here.

You have to be better to be equal, the saying goes.

I think, sometimes, when you know you have it easier in some ways, you force yourself to have it harder in other ways. Sometimes, when you’re told you have it easy, you disregard the ways in which you still have it hard. Sometimes, when you see the dreams your parents either did not achieve or did not even begin to dream up, you grow up with a sense of urgency to do what they did not get the chance to do. That applies to both the things they wanted and the things they dreaded.

Because my dad always felt that he had lost so much time, I wanted to be good with mine, and ironically, I always feel like I’m behind. Plus he was always telling me not to let the years get away from me. So I have always wanted to do the things that he could not do and not to waste the opportunities that come my way. But I believe that many of us can agree that it’s hard to reconcile the timelines for what we want with the milestones that others expect of us.

At the same time, I wrestle with the discomfort of knowing that while my intention is to be someone my dad would be proud of, my reality might be that I am someone who always aggravated his insecurities. If he were still alive today, would he be proud of me? Would he disapprove of my life choices, to choose the harder but (for me) the more rewarding path of becoming an artist and entrepreneur? Would he be insecure and even passive aggressive about the things that he could or would never do, that I can? Would we still be warring with each other’s contradictions, with both of us being stubborn, and with him still angry that his authoritarian views didn’t work on the daughter he pushed to be independent, observant, and strong?

Would I have made the same life choices if he were still alive? What if certain decisions, realities, and hard-but-very-real-life-and-death-questions hadn’t been pushed upon me at an early age? Would he, as a man who wanted his daughter to be strong, secretly resent all the ways in which his baby girl does not, and maybe never did, need him?

It’s also possible that none of these questions are worth asking, and some may even be draining or damaging. I have a good enough memory to draw connections and correlations between what is happening in our current social and political climate and what was happening when my dad was my age. But it would be a disservice to myself and the potential of the future, to compare my timeline too much with his, with my mother’s, or with anyone else’s, especially if we have each sought different fulfillments and life milestones.

Not to mention, things are already different. At 29, he was pursuing a new education. At 29, I am getting to share mine.

If I could let my dad know anything, it is that I do all the things I do out of love and respect and a desire to make things better, and that I am trying to do the best I can with what life has given me. History, with all its beauty, pain, trauma, and flaws, has given me only gifts. The qualities he thought were the worst about him have become the best about me. I believe it is our job, as people, to treasure what our parents gave us, and to equally treasure the need and the drive we have to fulfill what they did not give us.

When I look at what I have done thus far, I do not believe that I have done better than what others are capable of. If anything, I might have an above average awareness of the long-term game we each need to play. I know that I have roots and that roots require watering to keep their strength. I know that this is especially a challenge for anyone whose roots have needed to travel far for them to be here.

Each of us is still taking care of the seeds that were planted before us. Each of us must plant, share, and identify new seeds in our communities, to have gratitude for the gifts of history and to cultivate those gifts. Each of us must develop the insight to know the difference between growing a tulip and growing a tree, and the patience needed to address that difference fairly.

Each of us must know to study the past–not always to understand it–but to know that if we don’t understand, it’s because things are already different from the times when people thought “their present”/”our past” made sense. But things have changed. And things will continue to change. That, we must believe.

I hope, that if we are to do that, the trees of the future will bear fruit long after any of us here today are gone.

February Updates

- Thank you to the Capital Times in Madison for interviewing me about my artistic practice and project at the Central Library. It’s great to have a chance to share a bit of my creative story. The full Q&A is transcribed here.

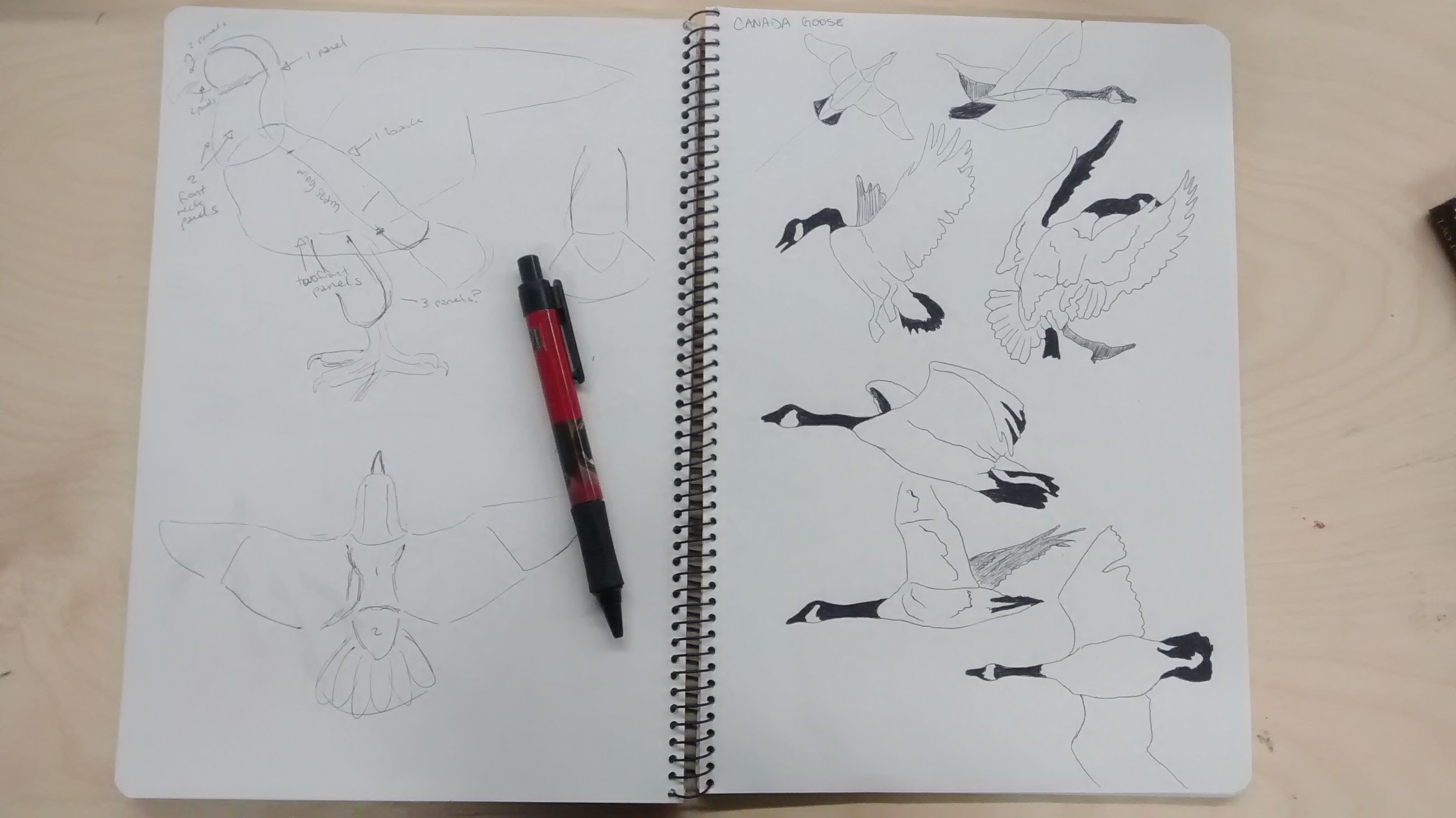

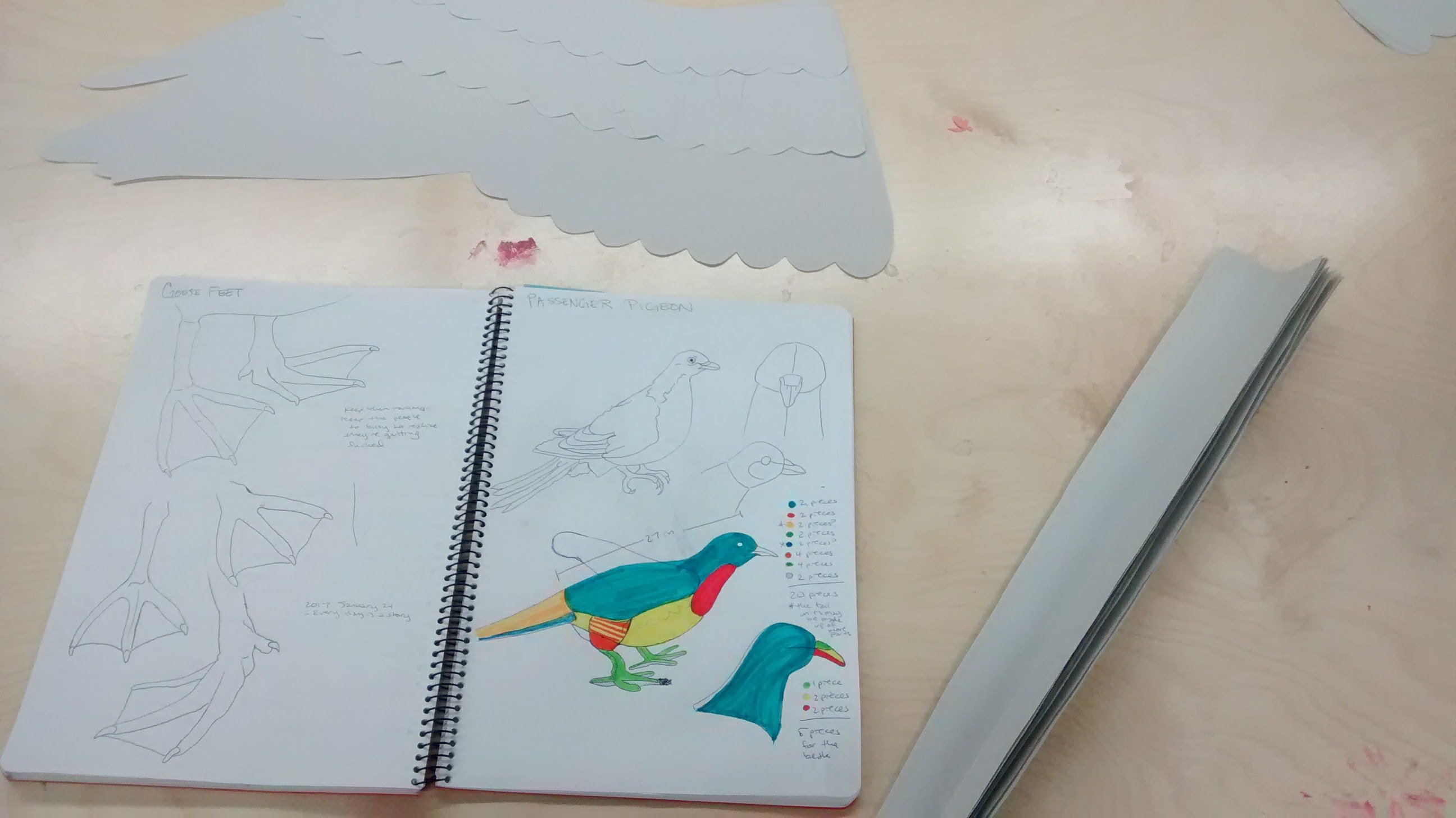

- I have entered Phase Two of my project, In Unison, for the Bubbler art residency at Madison Central Library, and am asking people to come join us for community sewing days, to help cut and sew patterns and bring these fabric birds to life. Sign up with a friend for one of the group sewing days online!

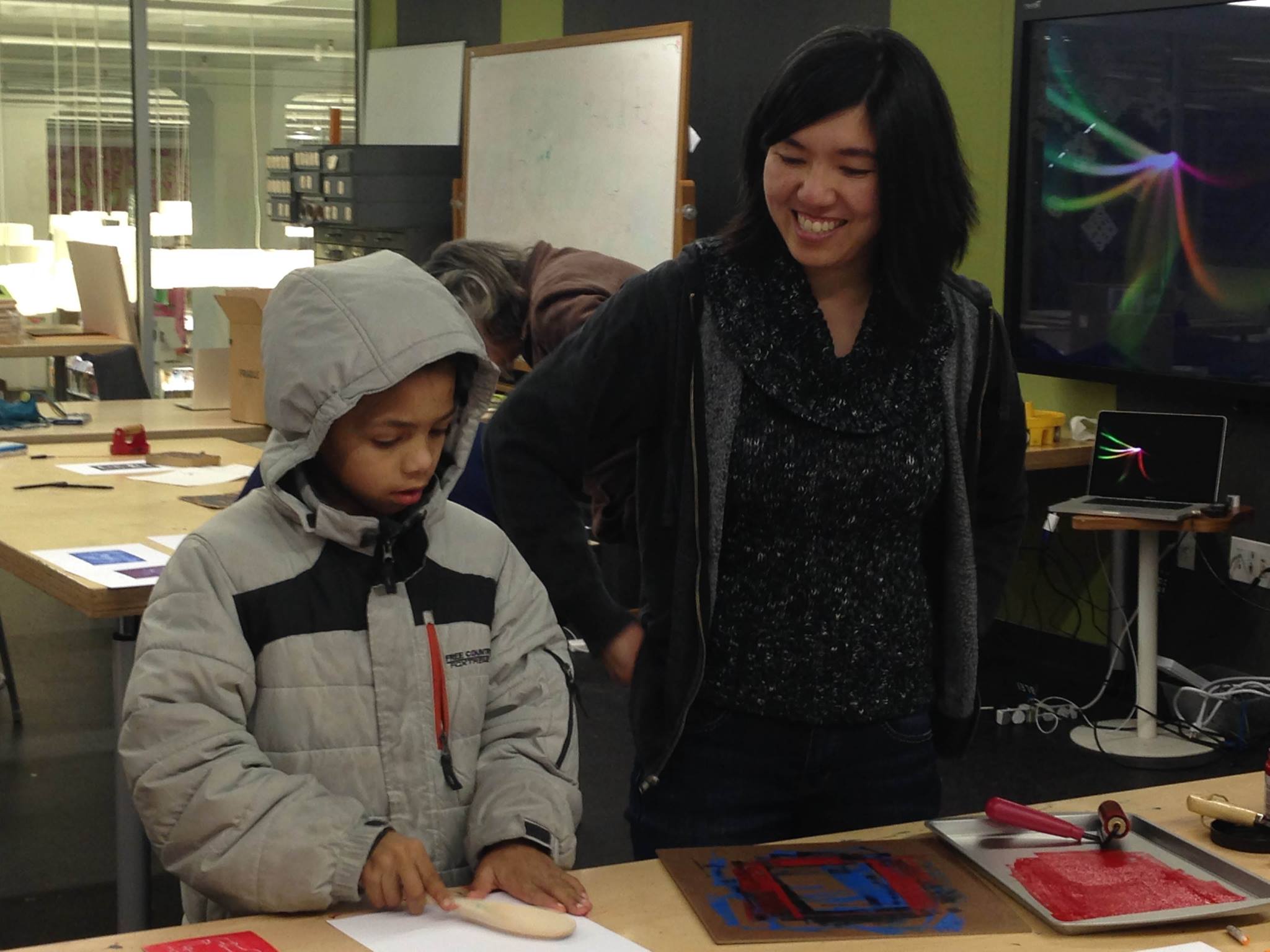

- I have started teaching two classes in Milwaukee, as part of two public art projects to be completed by May and June. I’m going to take this moment to say, I really enjoy teaching. :)

- I’ve started an activist book club with a group of people in Madison. Our first book will be The Lifelong Activist, by Hillary Rettig, available for free online or purchasable as a hard copy. Send me a message if you’re interested in joining up with us! We’ll be meeting biweekly.